Tip of The Spear

How Howard Knob kickstarted the climbing conservation movement.

By Andrew Kornylak

On November 5, Access Fund Executive Director Heather Thorne stood on a summit in Western North Carolina with a group of staff and board members from the Carolina Climbers Coalition (CCC). They had all topped out on a craggy point at Lower Ghost Town, one of the best climbing areas in the state. Surrounded by autumn colors and dramatic views of the Hickory Nut Gorge, CCC Executive Director Mike Reardon popped a champagne cork and a cheer went up. With that, another major climbing area was secured thanks to the work of a local climbing organization (LCO) and Access Fund.

Much of the climbing in the Southern U.S. is on private land, and climbing access there has been hard-won through patient and shrewd relationship-building with landowners. In the South, the biggest wins are usually acquisitions of private land. Each of these represents decades of partnerships between LCOs, landowners and other conservation organizations. Building on this legacy, another dramatic acquisition is in the works in North Carolina that is a testament to the power of these partnerships.

Overlooking Boone, North Carolina, the mountaintop of Howard Knob had been a popular local bouldering spot since the ‘70s, and the practice climbing area for the Appalachian State University’s Outdoor Programs. In 1993, a developer purchased the 74 acres surrounding the mountain’s summit–which included most of the best climbing—and announced plans for a subdivision. Boone local Joey Henson spearheaded a campaign to secure public access to the boulders with a scrappy community protest, using his beat-up house at the base of the mountain as a base camp. When that didn’t work, Henson and his friend Jeffrey Scott started the Watauga Land Trust, reaching out to other organizations for help.

Boone residents protest Howard Knob development plans July 1995.

Rick Thompson was a New River Gorge climber who had just moved to Boulder, Colorado to take the role of Access and Acquisitions Director of Access Fund. Thompson immediately started getting calls from Henson.

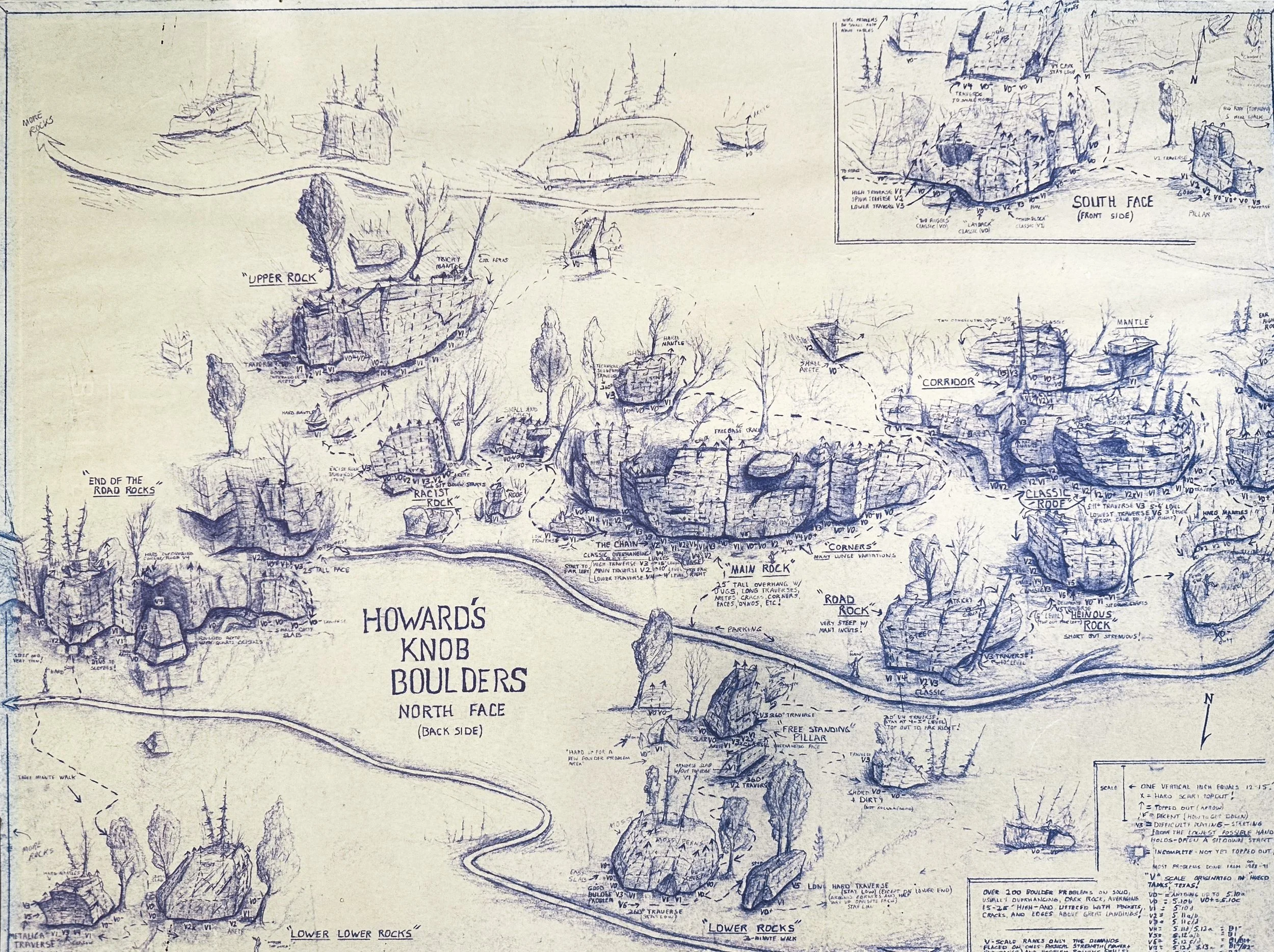

“He was always trying to get me to come back,” says Thompson, “So about a year or two into that position, I made the trip to Charlotte, drove up to Boone and hung out with Joey for about three days. I really got to see Howard Knob up close. Joey had created these hand-drawn maps of the Knob that were just a really magnificent piece of artistry. It was inspiring to see how much dedication Joey had, trying any way possible to get Howard Knob open for access.”

Joey Henson’s original guide to Howard Knob.

That commitment inspired Access Fund to commit $2500 towards an appraisal fee with an eye toward a possible public acquisition. Locals were motivated to keep the fundraising ball rolling.

Jim Horton was a busboy then at the Hound Ears Club, a posh gated community on another rocky mountainside. He and Henson thought it would be a great site for a little climbing competition.

“Everyone told me it was crazy, that they would never allow that to happen,” says Horton, “Joey was one of the few people that actually said, "Dude, you should just go for it to ask and see what happens." So I put a plan together, went in and talked to the club manager. He came to my bar one day and I rattled on for about a half hour at this big list of notes, and when I stopped talking he just goes, "Yeah, sounds good to me." So that's how we got started.”

Climbers at the 12th Hound Ears Competition October 2005 © Andrew Kornylak

The first Hound Ears Bouldering Competition in 1994 drew about a hundred people and provided the seed money to help the Watauga Land Trust become a real organization, with an office, a telephone, and a computer. Henson and Scott even started a community newspaper on Earth Day of that year called The New World News And Views. More importantly, people took notice, including the developer.

John Sherman devotes a whole section to Howard Knob in his bouldering road trip chronicle published that year, Stone Crusade, ending on a hopeful note: “Even the developer, with whom locals were initially on poor terms, became eager for the land to become a park, if a mutually agreeable price could be settled upon.”

Access Fund soon pledged $15,000 towards a serious acquisition.

Things were moving quickly. That same year, a rumor was spreading that North Carolina State Parks would close climbing access to some of the bigger cliffs in the state. Buoyed by the energy around Howard Knob, in January 1995, about a hundred concerned climbers held a meeting with park officials in Charlotte and formed the Carolina Climbers Coalition. The CCC began working that angle with help from Access Fund.

Back at Howard Knob, as The New World details in an update from later that year, “bulldozers began moving in June, cutting the first road across the south side, partially burying the main boulders of this slope, including the practice boulders… Several individuals chose to take action and climb trees in the path of the bulldozers.”

“Yes, that was us,” Henson laughs. “It may seem radical, but we felt there was a legitimate reason. The county inspector couldn’t actually determine the property line between public and private land, but the developer planned to start clearing the land anyway. How could we let them do that?”

He and Scott felt direct action was the only way.

“It was actually Jeffrey that went up first. I pushed him up the tree, teaching him how to double back his harness and hitch himself to the tree while the bulldozers were bearing down on us. That was a very tricky moment!”

By the weekend, about a dozen protesters gathered there while Scott and a few others stayed in the tree. Negotiations stalled, but the tree sits encouraged the next level of the movement. Word got out, and soon enough, almost a thousand people marched in the streets of Boone celebrating the cause, punctuating the day with a voter registration drive. Within a week, citizens, town leaders and local politicians had formed a community board to formally discuss the situation. The climbers even arranged a $50-a-plate dinner at the Broyhill Civic Center to facilitate it. By the end of it all, construction paused and almost $20,000 was raised for the war chest.

Henson was—and still is–a legendary keeper of climbing knowledge, some of it recorded onto hand-drawn maps of climbing areas known to only a few. He knew well that raising awareness of an area risked his own de facto access. But, as he puts it, “Sometimes, you have to publicize an area to save it.”

The campaign to save Howard Knob sparked an access revolution in the South that continues to this day. In 2002, Horton teamed up with Chad Wykle from Tennessee and Adam Henry from Alabama to combine three regional climbing competitions into a months-long festival, the Triple Crown Bouldering Series. Over the years, with support from Access Fund from the very beginning, it became the main fundraising engine for southern LCOs, and a yearly heartbeat of the climbing community. The effect was enormous.

“In the South we had to develop all the right skills to be able to either acquire land or negotiate our way onto property with partnerships,” says Wykle. “Access Fund has said it before: we were like the tip of the spear; an example for them to use and talk to other areas around the country and let them know that there's a path to success. Here's a road map that you can follow to create permanent access in areas across the country.”

Some areas seemed always out of reach, but climbers pressed on.

“We haven’t been able to save Howard Knob yet,” Boone Climbers Coalition President Mike Trew said in 2019. “We’re still trying! But we’ve been able to save a lot of other areas with the proceeds from the competitions.”

Meanwhile, the Watauga Land Trust continued to grow, bolstered by continuing support from Access Fund.

“Happy New Year, Rick!” The Trust’s Executive Director Michelle Merrit (now Michelle Leonard) wrote to Rick Thompson in 1998. “We have expanded our board and nominated officers… You have been such a great mentor! I appreciate all of your support and enthusiasm. Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!!!”

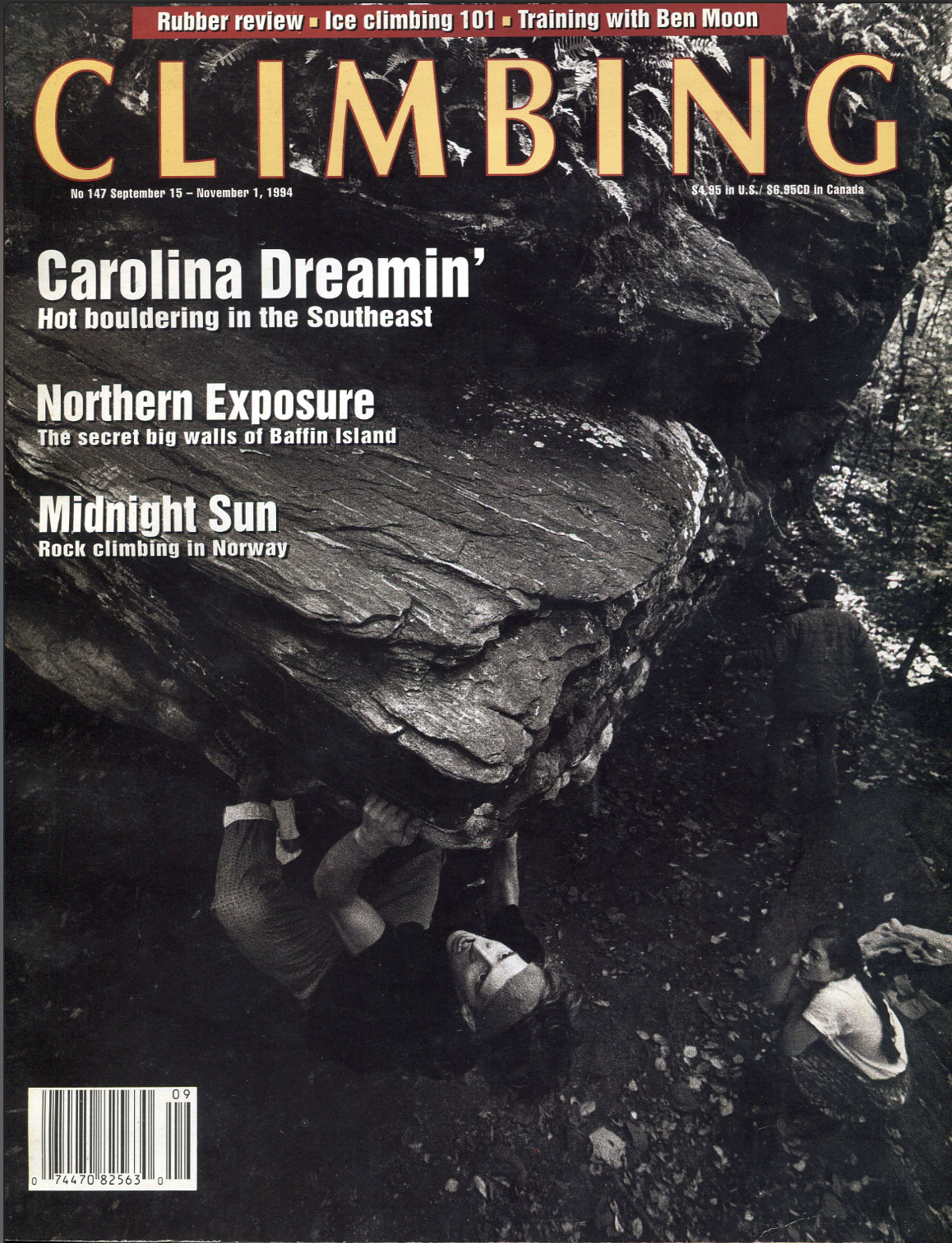

Howard Knob on the cover of Climbing Magazine issue 147 in 1994.

In 2010, after a previous name change to reflect an expanded scope outside of Boone, High Country Conservancy merged with Blue Ridge Rural Land Trust to form the current Blue Ridge Conservancy. Prior to the merger, longtime climber Eric Hiegl began working at the Conservancy as Director of Land Protection. In the years since they’ve seen great success, conserving over 26,000 acres of land throughout seven North Carolina counties for preservation and recreation.

They never forgot about Howard Knob.

“Jeffrey Scott was one of the first people I met when I moved to Boone in 1999,” says Hiegl. “He loved to tell stories and talk about Howard Knob, and a couple times every year we’d have climbers and other folks ask, "when are you going to get Howard?"” He laughs. “So it has been on my mind for 26 years. It was always on our to-do list.”

This Fall, Horton and Wykle announced that the Triple Crown Bouldering Series would come to an end. The LCOs that the Series helped fund over the years have now become fully-developed. There's much more awareness–and buying power–in the community around access. It was time for a new generation to take the lead.

“It’s like all the climbers have become adults,” says Horton. “There’s fresh blood, fresh ideas. I look forward to seeing where it goes in the future.”

When the future finally arrives, it’s always unexpected. Just days before the last Triple Crown comp kicked off at Hound Ears, Horton got a call from Hiegl. After a 32 year saga, Blue Ridge Conservancy was under contract on Howard Knob.

Horton was stunned.

“We’ve had such mixed feelings about ending Triple Crown, and feeling a little bit down about that,” he says. “Then, to find out our initial goal that started this whole thing so long ago was about to happen…”

Wykle completes the thought.

“It was surreal. Supernatural even. It seemed it was meant to be.”

It could easily have been different. Without the motivating access issue at Howard Knob, there’s no Hound Ears Bouldering Competition. Without Hound Ears, there’s no Triple Crown Series. The knowledge and confidence that was gained in those years culminated in over half a million dollars raised for the SCC, CCC, and Access Fund, mostly through small donations and generous industry sponsors. This money went toward dozens of climbing acquisitions, the largest of which—Laurel Knob—was the catalyst for Access Fund’s current acquisition model and Climbing Conservation Loan Program program.

As climbing has become more mainstream, more normalized, and other organizations have added public access as one of their conservation values, climbers have become less of a liability and more of an asset to land managers.

"Access Fund has spent years bridging the gap between climbers and the broader conservation community" says Thorne. "Even though climbers played an outsized role in the environmental movement in the U.S., we have not always been included in the conversations around meaningful conservation efforts, rather left at the margins. That narrative has changed and we are looking at an exciting future where climbing is treated as a conservation value on a landscape.”

Without the spark of Howard Knob, all that energy could have remained latent.

“There are about 120 access projects in the pipeline at any one time and only a few staff to work on them,” says Thorne. “Many of these projects are very complex, and some simply stall out due to a landowner being unresponsive or uninterested in opening up access, disagreement over the sale, inability to secure a recreation easement, or other factors. Howard Knob was one of those projects with daunting odds, but the commitment from climbers and conservationists paid off!”

“It really embodies the deep commitment it can take to see a successful preservation effort,” says Thompson. "It is never overnight. It may take two or three generations of climbers to succeed eventually. That’s how important long-term commitment is.”

For Henson, commitment is easier in partnership.

“You need a cohort. One becomes two. Two to four; four to eight. Soon there are a thousand people marching down the street.”

The march has started and right now our partners at the Blue Ridge Conservancy are under contract to purchase Howard Knob. To make it to the finish line and permanently protect this historic and treasured boulder field, they need the support of the climbing community.

The family of Rob and Beverly Holton, and Holton Mountain Rentals, has generously offered to match donations of $50 or more to this project up to $100,000. This means that when Blue Ridge Conservancy has raised $100,000 from the community, they'll actually have achieved $200,000 thanks to this generous matching gift. Please consider making a donation to Blue Ridge Conservancy to unlock this very generous gift from the Holton's.

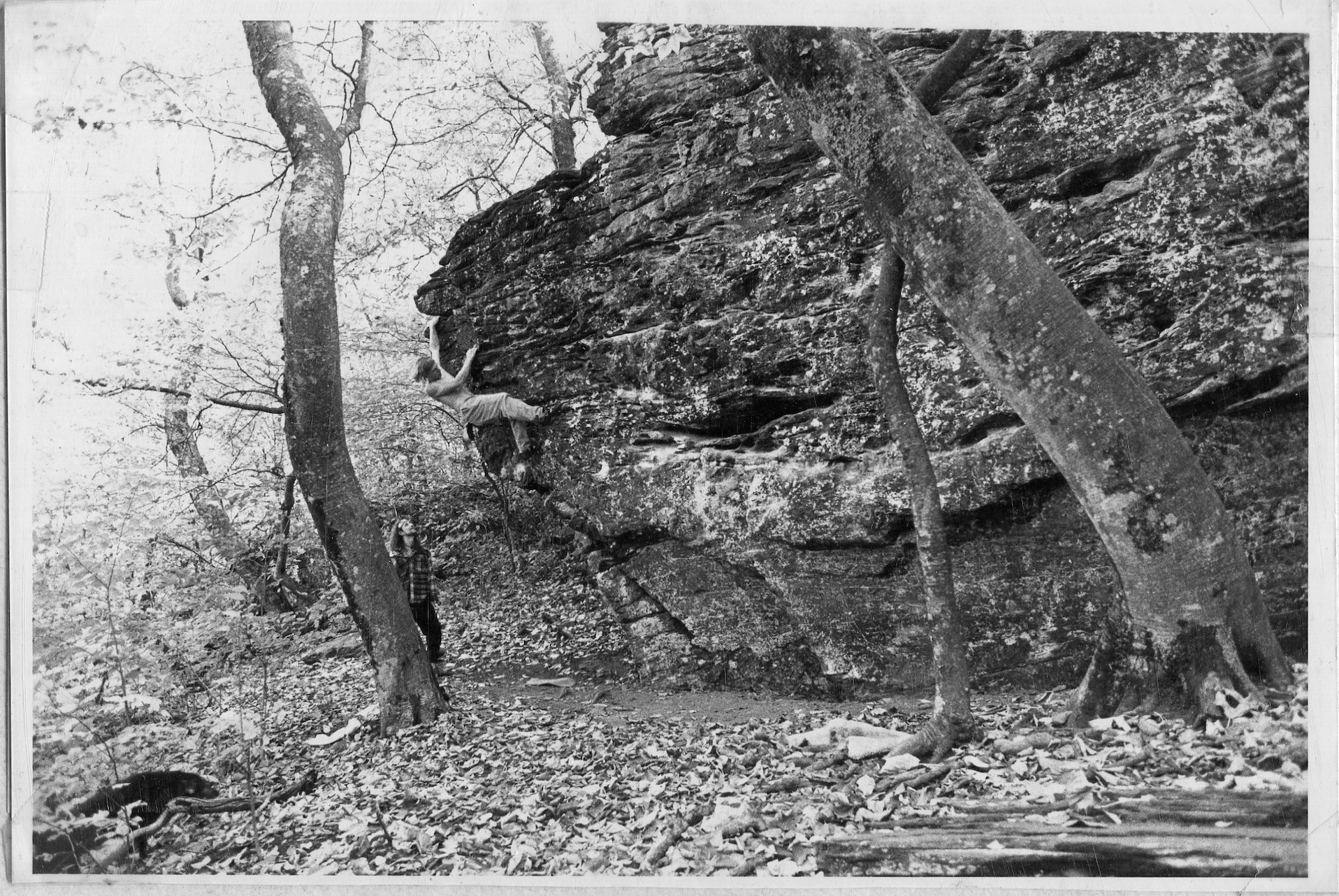

From the archives: Climber at Howard Knob before the 1993 closure.