By Gavin Feek

There’s a gulch on Oak Flat—a mesa in central Arizona held sacred by the San Carlos Apache and popular with local climbers—with boulders balanced on boulders like giant stone pillars carved from volcanic tuff. Under the boulders, dry creek bed sand wends its way around natural caves and formations carved millions of years ago. The San Carlos Apache believe there are ancient corridors here that have protected their ancestors during great floods of the past, and that they’re to return to Oak Flat for protection when the rains come again.

But Oak Flat might be gone soon. And with it the caves and corridors, boulders and formations, and hundreds of archaeological sites built by its original people. In its place would be a hole, destined to eventually be 1.8 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep: over twice the size of nearby Meteor Crater. A mining company called Resolution Copper found copper there, thousands of feet below the surface. They’ve proposed a technique called block caving, which involves digging tunnels beneath a deposit, allowing the overlying rock to cave in and expose the ore. For the past two decades, a David and Goliath story has unfolded between the local Indigenous tribes, climbers, and conservationists who wish to preserve Oak Flat, and the mining company that wants to destroy it.

In November 2021, Wendsler Nosie of the San Carlos Apache Tribe wrote a letter to then-President Joe Biden and hand-delivered it to the White House. President Biden wasn’t available, so he left it with a guard. The letter informed the president that Nosie would no longer be living on the San Carlos Indian Reservation in Arizona, where he was born and had lived his entire life. When he returned from Washington, he left the reservation and walked home, 70 miles to Oak Flat, or Chích’il Bił Dagoteel, as it was originally named. The spot is sacred to Nosie, not only because his people lived there, but because they continue to heal and worship there. “Angels live here,” Nosie told me while sitting on a volcanic rock near the Oak Flat Campground, surrounded by manzanita, scrub oak, and bats in early September 2025.

Wendsler Nosie talks about the significance of Oak Flat to the San Carlos Apache. © Gavin Feek

The 1852 Santa Fe Treaty between the United States and the Apache people states that the Western Apache were to retain partial ownership of the lands in and around what is now known as Tonto National Forest. In 1955, President Eisenhower signed an order including Oak Flat in the Tonto National Forest, ensuring it would be protected for “public use.” But in 1995, the Magma Copper Company discovered a large underground copper deposit beneath Oak Flat. In 1996, Australian mining giant BHP purchased the Magma Copper Company, and set its sights on that deposit, putting in motion a chain of events that Indigenous groups, environmental groups, local advocates, and Access Fund have been battling ever since.

In the early eighties, a Phoenix climber named Jim Waugh found himself at Tucson’s Beanfest enjoying a bouldering competition. As he watched the Tucson climbers compete, it occurred to him that nobody he knew bouldered in Phoenix. “Maybe because it was so hot,” Waugh told me. So in the spring of 1983, Waugh kicked off the annual Phoenix Bouldering Contest at Camelback Mountain. There were 35 competitors. But after six years of going back and forth between Camelback and South Mountain, the competition had grown.

“It started as a grassroots event, and then it became an international event,” Waugh said. “People were coming from all over the world. It was a get-together, a party, and a bouldering comp.”

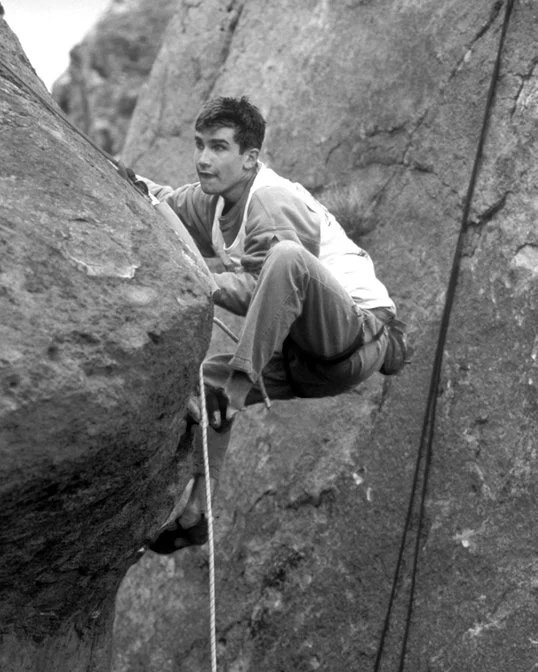

Chris Sharma climbs at an early Phoenix Bouldering Contest in 1997.

In 1988, Waugh needed a better spot to host his contest—with more land and a lot more boulder problems. He’d heard whispers about boulders at Oak Flat but hadn’t been up there himself. “Nothing was really known, nor established at the time,” Waugh said. “I went out there, and oh man, I literally found a goldmine.” He established over 300 bouldering routes in less than eight months at Oak Flat.

In 1989, the contest officially moved to Oak Flat, and people came from all around. Jim and his team developed more problems and, within a few years, there were over 1,500 established routes. By the mid-90s, pro climbers were beginning their careers there.

“My first year at the competition, I was a kid,” Tommy Caldwell told me over the phone from his home in Lake Tahoe. “I just thought I would come climb, and I didn’t think I was that good. Then I came in second to Timmy O’Neill. Between that and one other competition, it was my coming of age. I was like, ‘Oh man, I’m a competitive rock climber.’”

To make the bouldering competition work, Waugh had to work closely with the nearby Magma Mine to ensure everything functioned properly. The Magma Mine had moved onto land adjacent to Oak Flat (which later became Forest Service land) in 1910 and kept operations going until 1996. The mine gave Waugh permission to use their roads and overflow parking lots for camping, and volunteers would bus people back and forth to the campground.

In 2004, foreign mining company RioTinto joined BHP and formed Resolution Copper to take over the Magma Mine and explore the deposit under Oak Flat. One of the first things they did was get rid of the Phoenix Bouldering Contest. “They said, ‘Look, you guys have to go away,’” Waugh told me. “Then a lot of people started getting involved.”

A billboard in Superior, Arizona. Apache Leap rises directly behind with Oak Flat beyond. © Gavin Feek

Resolution's Plans to render Oak Flat into a giant hole became public in 2005 when Arizona Senator Jon Kyl introduced a bill to transfer the land to the company. That’s when Access Fund, in concert with the San Carlos Apache Tribe and several other conservation organizations, officially joined the fight to save Oak Flat. “We testified on Capitol Hill in a hearing, we wrote multiple letters to congress, and we were part of blocking those bills for a decade,” Access Fund Deputy Director Erik Murdock told me.

Resolution tried again in December 2014, when John McCain attached a deal to transfer 2,400 acres—including Oak Flat—to Resolution Copper onto a “late-night rider” in a national defense bill. Congress had one hour to review thousands of pages before approving. “John McCain met with Senator Mitch McConnell in the middle of the night, got the rider into the National Defense Authorization Act—a must-pass bill— with nobody around. And literally the president signed it soon thereafter,” Murdock said.

But the bill required the Forest Service to write an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), and to collect public comments before the transfer could be completed. In 2015, the San Carlos Apache Tribe sued the Federal Government to block the land transfer, delaying completion of the EIS.

As protests to the land exchange mounted, Resolution Copper worked with multiple environmental and recreation advocacy groups to offer alternatives to opposing the mine proposal, aiming to satisfy elements of the EIS. They built trails for mountain bikers, rerouted the Arizona Trail, and traded land to appease environmental groups. They even paid a prolific route developer to give climbers an alternative to Oak Flat. At one point, Resolution Copper offered to purchase The Homestead, a limestone sport climbing area, for Access Fund, if they would drop the fight to protect Oak Flat. But Access Fund turned them down and bought it themselves. “We almost have it paid off,” Murdock told me.

With the EIS still blocking the sale, then-Access Fund Policy Analyst Curt Shannon took part in meetings in Globe, Kearny, and all the little mining towns around Oak Flat, working behind the scenes on the environmental review process, and submitting comments at every opportunity.

In the final days of President Trump’s first term, his administration asked the Forest Service to fast track the EIS and initiate the official transfer of Oak Flat to Resolution Copper. But Access Fund and The Apache Stronghold, a collective of members of the San Carlos Apache, sued the Federal Government in separate lawsuits to block the transfer.

The Campground Boulders on Oak Flat. © Gavin Feek

“It goes on death row,” Nosie told me. “And then we get it out [of death row]. Then it goes on death row again, and then we get it out. But it does damage.”

Access Fund’s case, still active four years later, hinges on the EIS. “The Biden Administration came in and asked the BLM to audit the Forest Service EIS,” Murdock said. “They needed to address the deficiencies of the EIS that the Trump Administration released. The big one was water.” Resolution’s plans have the potential to pollute nearby aquifers, springs, and wetland habitats, as well as exhaust ground and surface water supplies.

In April 2025, the Trump Administration, in its second term, again ordered a fast tracking of the land transfer. In August, a Ninth Circuit judge issued a temporary injunction to stop Oak Flat from being transferred to Resolution Copper.

“We have a January 7 court date,” Murdock said. “And if the Ninth Circuit Court decision doesn’t rule in our favor, we can keep going. We can appeal.”

“Until they blow the hole, there’s still time,” Nosie told me in Septemberm “Once they blow the hole...there’s no more time. But I’m not done here.”

Waugh was well aware of the Apache connection when he started establishing routes at Oak Flat. But it was a recreational area—a big one with plenty of possibilities. He made sure that every bit of trash was picked up after each contest by organizing a massive cleanup day. He even worried about the bolts and chalk marks, and the few manzanita bushes he’d cleared to make approach trails.

When I asked him how it felt to imagine it all caved in, a thousand feet below, he was wistful. “It was a major part of my life. I’ve done a lot of things, but the truth of it is, if my name comes up, it’s because of The Phoenix Bouldering Contest. So that will probably be my legacy.”

Caldwell thinks the mine has done a great job of making climbers forget about Oak Flat. “They’ve made people feel like it’s a lost cause,” he told me. Instead, Caldwell views the climbing as Oak Flat’s potential saving grace. “The fact that there’s climbing there gives climbers the chance to weigh in on a bigger issue—that’s how I look at it,” he said. “You’ve got to root for the underdog, especially when it’s so obvious we have right on our side.”

Wednesday, December 3rd 2025 Update:

Newly elected Congresswoman Adelita Grijalva (AZ-07) introduced her first piece of legislation in Congress—the Save Oak Flat from Foreign Mining Act. This landmark bill would repeal the 2015 controversial land exchange law of the 2,400 acre sacred landscape to foreign mining company Resolution Copper.

Access Fund commends Representative Grijalva for this critical action to reverse a deeply flawed land exchange and safeguard one of the nation’s most valuable cultural and recreational landscapes.